Lifting the kimono on Japanese erotic art - in pictures

A

new exhibition dedicated to shunga, the sensual art of samurai Japan,

opens in London this week. From carnal clinches to filthy fantasies, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art at the British Museum has enough to titillate all tastes. It runs from 3 October to 5 January 2014

The joy of art: why Japan embraced sex with a passion

Japan

is the only country in which erotic art – 'shunga' – has been

mainstream. A new exhibition at the British Museum shows how sex was

often allied to comedy and political subversion

Nature worship … Ako to Ama (Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife) by Hokusai

The image of an ecstatic woman having cunnilingus administered

by an octopus would seem to be far removed from the mainstream of any

major artistic tradition. Yet this is one of the most famous pictures by

Hokusai, perhaps the greatest Japanese print artist of his or any other time.

Rembrandt did some etchings of couples having sex. Picasso did many erotic pictures, as did Degas, Toulouse Lautrec and Rodin. George Grosz

did some remarkably kinky watercolours. But erotic art was never in the

mainstream of European art, or any artistic tradition that I can think

of, except that of Japan.

Even ancient Greece was not quite in the same league. Almost all the major Japanese artists of the 17th and 18th centuries depicted sexual intercourse – featuring men, women, foxes, donkeys, ghosts and even the odd stingray.

These were not minor works contrived for the secret pleasure of a few like-minded libertines.

Women enjoyed them as well as men.

Thousands of books were published with erotic prints. And although sometimes frowned on by government officials, they were bought in large numbers by people of all classes.

Spring pictures, or "shunga", were almost as numerous as pictures of landscapes, famous beauties or animals.

Unlike, say, the kabuki theatre, shunga were not even confined to the beautiful but often raffish culture of the brothel districts: artists of the noble Kan¯o school painted erotic scenes as well.

Sex was not a vice, even if breaking social taboos (running off with someone else's husband, say) could have serious consequences.

These taboos had little to do with sexual preference: many pictures in the splendid exhibition at the British Museum show men having sex with men.

One of the earliest erotic handscrolls, from the 15th century, shows a Buddhist priest casting longing glances at his young acolyte. Indeed, among some samurai, male love was considered superior to the heterosexual kind. Women were necessary to produce children, but male love was purer, more refined.

The question is why were Japanese – compared not just with Europeans, but other Asians, too – so much more open to depicting sex? One reason might be found in the nature of Japanese religion. The oldest native ritual tradition, Shinto, was, like most ancient cults, a form of nature worship, to do with fertility, mother goddesses, and so forth. This sometimes took the form of worshipping genitals, male as well as female.

Whereas in many cultures, later patriarchal traditions – Christian, Confucian, or even Buddhist – buried older fertility cults, Japanese nature-worship never really disappeared. There are still Shinto shrines today, where women go to stroke wooden phalluses in the hope of getting children. In certain rural festivals, phallic objects are carried through the streets to be joined with sacred vulvas produced from other shrines.

This could be one explanation for a convention that might strike people as curious: the extraordinary, even grotesque size of male and female genitals in Japanese erotic art. Even though realistic representation was rarely the aim of classical Japanese painting, the genitals in most shunga seem particularly out of whack.

Here is a quote from a 13th-century text: "Look at those erotic paintings made by old masters. They depict the size of 'the thing' far too large. How could it actually be like that? If it were depicted in its actual size, there would be nothing of interest. For that very reason, don't we say 'art is fantasy'?"

Reading this item in the exhibition catalogue, I am reminded of a striptease show I once saw in Kyoto, the ancient imperial capital. While the nude dancer squatted on the edge of the stage, magnifying glasses were handed out to the men sitting in the front row. These aficionados proceeded to inspect every anatomical detail in solemn silence. To call this a religious rite would be pretentious. But it was more than just an entertaining fantasy.

Erotic images sometimes had a talismanic function. Prints were tucked inside a suit of samurai armour to lend strength to the warrior who wore it. Merchants used them to ward off fires in their storehouses. As is true of so much in the Japanese tradition, this goes back to Chinese sources. In fact, the term "spring pictures" is originally Chinese: chun-hua. Already in the sixth century, Chinese aristocrats owned erotic pictures. Another Chinese term for them was "fire-avoiding pictures".

However, China being China, the purpose of these works was didactic rather than hedonistic. They were mostly sex manuals, meant to instruct men in particular how to conserve their vitality and improve their health. Human vitality is expressed in the word "qi", meaning life force or vital energy. Semen was thought to be a concentration of this life force, and it was best to conserve it by avoiding ejaculation. To what extent Chinese men lived by this rule, I do not know. But Chairman Mao was probably not the last Chinese potentate who believed that his longevity required frequent sexual communion with much younger women.

The Japanese were far less bothered with the medical aspects of erotic art, and more interested in the possibilities of pleasure. A 16th-century Japanese doctor, named Manase Dosan, translated an ancient Chinese sex manual, but as the scholar Aki Ishigami observes in her catalogue essay: "In place of the Chinese emphasis on maintaining health and longevity, it explained in detail how to enjoy sex." The same thing happened in art. Shunga, in prints and paintings, might originally have had a purpose in educating newly wedded couples, or fending off fires, or expressing cosmic harmony, but they were primarily meant to be enjoyed.

Another term for erotic images was warai-e, literally "pictures for laughter". There is a rich tradition of satire and comedy in Japanese erotic art. This type of laughter is not the sniggering associated with British drag shows or Benny Hill, which betrays a puritanical unease. Rather it shows a rebellious spirit against social conventions and a taste for the grotesque. Here, too, there is probably a religious angle, which might best be illustrated by one of the most ancient Japanese myths.

One day the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami withdrew into her cave in a huff, depriving the world of light. To entice her back, the gods staged an orgy outside the cave's entrance and one of them performed a striptease, which caused so much laughter among the gods, that Amaterasu couldn't resist emerging from her hiding place. And so there was light.

A remarkable number of erotic pictures are parodies of one sort or another. This was an important aspect of the culture of the pleasure districts in premodern Japan. Prostitutes in expensive brothels adopted the names of grand aristocratic ladies from the 11th-century Tale of Genji. Ancient emperors, samurai rulers and famous nobles were depicted in all kinds of erotic entanglements in shunga. Other prints showed pornographic versions of the various stages of Buddhist enlightenment (lecherous priests were a popular subject anyway).

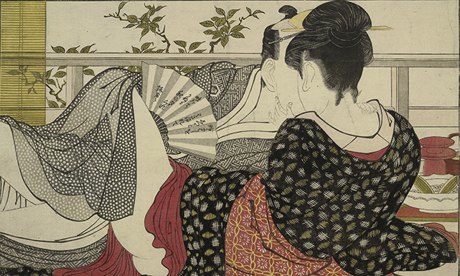

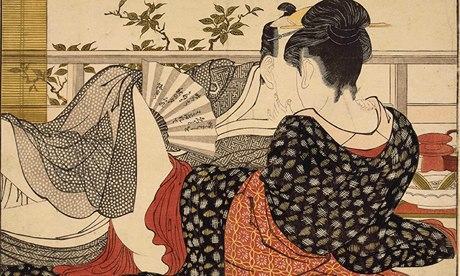

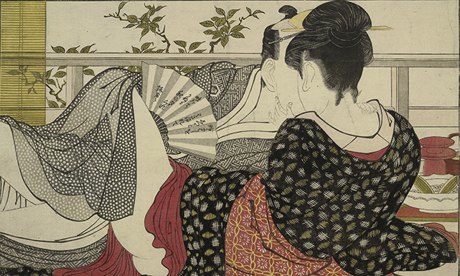

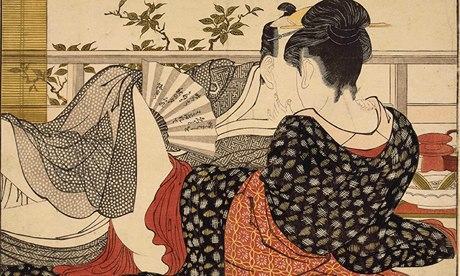

Lovers in the Upstairs Room of a Teahouse, 1788, by Kitagawa Utamaro. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

Lovers in the Upstairs Room of a Teahouse, 1788, by Kitagawa Utamaro. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

Since Tokugawa Japan (1603-1868) was a highly authoritarian society, political satire was rarer, but not at all unknown. And it was the rebellious laughter at the expense of officialdom that got artists into serious trouble with government censors.

Nishikawa Sukenobu's salacious images of an 11th-century aristocratic ruler having sex with a famous poet showed sufficient disrespect for the social order that it might have provoked the ban in 1722 on erotic publications. Later, the great Kitagawa Utamaro got into trouble for poking fun at Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the 16th-century warlord who unified Japan. The point, then, was not sex per se, but political or social subversiveness.

The cat and mouse game between artists, using sexual imagery or grotesque caricature, and official censors continued until very recently.

One of the most notorious Japanese court cases of the 1970s surrounded the hardcore cinematic masterpiece, In the Realm of the Senses, directed by Nagisa Oshima. Specifically, it related to the book of still photographs from the film; the movie had already been butchered by the censors. Oshima was tried for "obscenity", but the real issue was his rebelliousness: he had always been a leftist critic of the political establishment. The case was less about public morals than about his politics. Or, rather, as Oshima himself put it, public morals were a highly political issue.

This was probably the case in 1722, too – without too much effect. Erotic art just went underground for a while. But it reoccured in a more serious way after 1868, when the old samurai order collapsed and was replaced by a modernising, westernising state. Modernisation along western lines – western clothes, a modern army, an overseas empire, a parliament, universities and so on – was meant to be a defence against the very western powers that Japan was mimicking.

Part of this effort was an official obsession with respectability. Old, "primitive" ribald Japan had to be cleaned up. Public nudity, mixed bathing, wild kabuki plays were all now disapproved of. So there was no way that shunga could remain in the mainstream. Indeed, in the eyes of the Meiji period (1868-1912) patriarchs, it would have been best to get rid of erotic art altogether.

The novelist Yukio Mishima likened Meiji Japan to a bourgeois housewife sweeping all the dirt away before guests come to call. Of course, much of this was superficial. Artists, in photography as well as painting and prints, continued to produce erotic stuff. Indeed, the most democratic period of prewar Japan, the "Taisho democracy" of the roaring 20s, was known for ero guro nansensu culture, short for "erotic, grotesque, absurd".

But the anxieties of the Meiji state, which came as part of westernisation, remained after democracy and freedom of expression had been restored, even strengthened after the second world war. As in the past, the censors were more worried about subversion and social disorder than sex. Cracking down periodically on pornography was a way for officials to show who was in charge. For a long time, censorship was focused on the very thing that make traditional Japanese erotica so distinctive: the genitals.

According to what might be an urban legend, middle-aged housewives and schoolboys in need of pocket money were hired to censor magazines, photography books and even serious art books featuring shunga, by scratching out any sign of genitalia. Drawing one's attention to these scratched, blotted and inked-over parts of the human anatomy had the effect of making the images seem more grotesque.

Fortunately, in recent years, the rules on genitalia have been relaxed. The shunga tradition has been revived in various modern forms. The photographer Nobuyoshi Araki has often stated that his pictures of strippers, prostitutes and nudes in a variety of unusual poses, not to mention his penchant for the grotesque, owe a debt to erotic art of the Tokugawa period. And the fact that the exhibition at the British Museum is supported by the finest scholarly institutions, as well as some excellent scholars from Japan, shows that spring pictures have been restored to the artistic mainstream, which is where they surely belong.

- Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art

- British Museum,

- Great Russell St, London

- WC1

- Starts 3 October

- Until 5 January

- Details:

020-7323 8299 - Venue website

Even ancient Greece was not quite in the same league. Almost all the major Japanese artists of the 17th and 18th centuries depicted sexual intercourse – featuring men, women, foxes, donkeys, ghosts and even the odd stingray.

These were not minor works contrived for the secret pleasure of a few like-minded libertines.

Women enjoyed them as well as men.

Thousands of books were published with erotic prints. And although sometimes frowned on by government officials, they were bought in large numbers by people of all classes.

Spring pictures, or "shunga", were almost as numerous as pictures of landscapes, famous beauties or animals.

Unlike, say, the kabuki theatre, shunga were not even confined to the beautiful but often raffish culture of the brothel districts: artists of the noble Kan¯o school painted erotic scenes as well.

Sex was not a vice, even if breaking social taboos (running off with someone else's husband, say) could have serious consequences.

These taboos had little to do with sexual preference: many pictures in the splendid exhibition at the British Museum show men having sex with men.

One of the earliest erotic handscrolls, from the 15th century, shows a Buddhist priest casting longing glances at his young acolyte. Indeed, among some samurai, male love was considered superior to the heterosexual kind. Women were necessary to produce children, but male love was purer, more refined.

The question is why were Japanese – compared not just with Europeans, but other Asians, too – so much more open to depicting sex? One reason might be found in the nature of Japanese religion. The oldest native ritual tradition, Shinto, was, like most ancient cults, a form of nature worship, to do with fertility, mother goddesses, and so forth. This sometimes took the form of worshipping genitals, male as well as female.

Whereas in many cultures, later patriarchal traditions – Christian, Confucian, or even Buddhist – buried older fertility cults, Japanese nature-worship never really disappeared. There are still Shinto shrines today, where women go to stroke wooden phalluses in the hope of getting children. In certain rural festivals, phallic objects are carried through the streets to be joined with sacred vulvas produced from other shrines.

This could be one explanation for a convention that might strike people as curious: the extraordinary, even grotesque size of male and female genitals in Japanese erotic art. Even though realistic representation was rarely the aim of classical Japanese painting, the genitals in most shunga seem particularly out of whack.

Here is a quote from a 13th-century text: "Look at those erotic paintings made by old masters. They depict the size of 'the thing' far too large. How could it actually be like that? If it were depicted in its actual size, there would be nothing of interest. For that very reason, don't we say 'art is fantasy'?"

Reading this item in the exhibition catalogue, I am reminded of a striptease show I once saw in Kyoto, the ancient imperial capital. While the nude dancer squatted on the edge of the stage, magnifying glasses were handed out to the men sitting in the front row. These aficionados proceeded to inspect every anatomical detail in solemn silence. To call this a religious rite would be pretentious. But it was more than just an entertaining fantasy.

Erotic images sometimes had a talismanic function. Prints were tucked inside a suit of samurai armour to lend strength to the warrior who wore it. Merchants used them to ward off fires in their storehouses. As is true of so much in the Japanese tradition, this goes back to Chinese sources. In fact, the term "spring pictures" is originally Chinese: chun-hua. Already in the sixth century, Chinese aristocrats owned erotic pictures. Another Chinese term for them was "fire-avoiding pictures".

However, China being China, the purpose of these works was didactic rather than hedonistic. They were mostly sex manuals, meant to instruct men in particular how to conserve their vitality and improve their health. Human vitality is expressed in the word "qi", meaning life force or vital energy. Semen was thought to be a concentration of this life force, and it was best to conserve it by avoiding ejaculation. To what extent Chinese men lived by this rule, I do not know. But Chairman Mao was probably not the last Chinese potentate who believed that his longevity required frequent sexual communion with much younger women.

The Japanese were far less bothered with the medical aspects of erotic art, and more interested in the possibilities of pleasure. A 16th-century Japanese doctor, named Manase Dosan, translated an ancient Chinese sex manual, but as the scholar Aki Ishigami observes in her catalogue essay: "In place of the Chinese emphasis on maintaining health and longevity, it explained in detail how to enjoy sex." The same thing happened in art. Shunga, in prints and paintings, might originally have had a purpose in educating newly wedded couples, or fending off fires, or expressing cosmic harmony, but they were primarily meant to be enjoyed.

Another term for erotic images was warai-e, literally "pictures for laughter". There is a rich tradition of satire and comedy in Japanese erotic art. This type of laughter is not the sniggering associated with British drag shows or Benny Hill, which betrays a puritanical unease. Rather it shows a rebellious spirit against social conventions and a taste for the grotesque. Here, too, there is probably a religious angle, which might best be illustrated by one of the most ancient Japanese myths.

One day the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami withdrew into her cave in a huff, depriving the world of light. To entice her back, the gods staged an orgy outside the cave's entrance and one of them performed a striptease, which caused so much laughter among the gods, that Amaterasu couldn't resist emerging from her hiding place. And so there was light.

A remarkable number of erotic pictures are parodies of one sort or another. This was an important aspect of the culture of the pleasure districts in premodern Japan. Prostitutes in expensive brothels adopted the names of grand aristocratic ladies from the 11th-century Tale of Genji. Ancient emperors, samurai rulers and famous nobles were depicted in all kinds of erotic entanglements in shunga. Other prints showed pornographic versions of the various stages of Buddhist enlightenment (lecherous priests were a popular subject anyway).

Lovers in the Upstairs Room of a Teahouse, 1788, by Kitagawa Utamaro. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum

Lovers in the Upstairs Room of a Teahouse, 1788, by Kitagawa Utamaro. Photograph: The Trustees of the British Museum Since Tokugawa Japan (1603-1868) was a highly authoritarian society, political satire was rarer, but not at all unknown. And it was the rebellious laughter at the expense of officialdom that got artists into serious trouble with government censors.

Nishikawa Sukenobu's salacious images of an 11th-century aristocratic ruler having sex with a famous poet showed sufficient disrespect for the social order that it might have provoked the ban in 1722 on erotic publications. Later, the great Kitagawa Utamaro got into trouble for poking fun at Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the 16th-century warlord who unified Japan. The point, then, was not sex per se, but political or social subversiveness.

The cat and mouse game between artists, using sexual imagery or grotesque caricature, and official censors continued until very recently.

One of the most notorious Japanese court cases of the 1970s surrounded the hardcore cinematic masterpiece, In the Realm of the Senses, directed by Nagisa Oshima. Specifically, it related to the book of still photographs from the film; the movie had already been butchered by the censors. Oshima was tried for "obscenity", but the real issue was his rebelliousness: he had always been a leftist critic of the political establishment. The case was less about public morals than about his politics. Or, rather, as Oshima himself put it, public morals were a highly political issue.

This was probably the case in 1722, too – without too much effect. Erotic art just went underground for a while. But it reoccured in a more serious way after 1868, when the old samurai order collapsed and was replaced by a modernising, westernising state. Modernisation along western lines – western clothes, a modern army, an overseas empire, a parliament, universities and so on – was meant to be a defence against the very western powers that Japan was mimicking.

Part of this effort was an official obsession with respectability. Old, "primitive" ribald Japan had to be cleaned up. Public nudity, mixed bathing, wild kabuki plays were all now disapproved of. So there was no way that shunga could remain in the mainstream. Indeed, in the eyes of the Meiji period (1868-1912) patriarchs, it would have been best to get rid of erotic art altogether.

The novelist Yukio Mishima likened Meiji Japan to a bourgeois housewife sweeping all the dirt away before guests come to call. Of course, much of this was superficial. Artists, in photography as well as painting and prints, continued to produce erotic stuff. Indeed, the most democratic period of prewar Japan, the "Taisho democracy" of the roaring 20s, was known for ero guro nansensu culture, short for "erotic, grotesque, absurd".

But the anxieties of the Meiji state, which came as part of westernisation, remained after democracy and freedom of expression had been restored, even strengthened after the second world war. As in the past, the censors were more worried about subversion and social disorder than sex. Cracking down periodically on pornography was a way for officials to show who was in charge. For a long time, censorship was focused on the very thing that make traditional Japanese erotica so distinctive: the genitals.

According to what might be an urban legend, middle-aged housewives and schoolboys in need of pocket money were hired to censor magazines, photography books and even serious art books featuring shunga, by scratching out any sign of genitalia. Drawing one's attention to these scratched, blotted and inked-over parts of the human anatomy had the effect of making the images seem more grotesque.

Fortunately, in recent years, the rules on genitalia have been relaxed. The shunga tradition has been revived in various modern forms. The photographer Nobuyoshi Araki has often stated that his pictures of strippers, prostitutes and nudes in a variety of unusual poses, not to mention his penchant for the grotesque, owe a debt to erotic art of the Tokugawa period. And the fact that the exhibition at the British Museum is supported by the finest scholarly institutions, as well as some excellent scholars from Japan, shows that spring pictures have been restored to the artistic mainstream, which is where they surely belong.

Erotic bliss shared by all at Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art

A world away from pornography, explicit Japanese shunga prints celebrate sex as a sensual act, and everyone has a good time

Sensual harmony ...

Kitagawa Utamaro, Lovers in the upstairs room of a teahouse, c.1788.

Photograph: copyright of the Trustees of the British Museum

Opulent eroticism curves and billows in this bold exhibition of shunga prints

made to entertain and arouse Japanese men and women between 1600 and

1900. Fantasy blossoms too: in a sensational picture by Hokusai, two octopuses make love to a fisherman's wife, their tentacles literally everywhere. Her face is ecstatic.

The curator of this delve into art's sensual history at the British Museum insists that pleasure is mutual in shunga. Early modern Japan was no feminist paradise, and the show does stress the harsh realities of the sex industry.

But in shunga prints, which were looked at by men and women and

treasured by married couples, everyone is having a good time. Lovers

bask side by side in kimonos and you have to look a moment to see what

they're up to under the brightly coloured folds. Or they twist into

spectacular conjunctions that create wondrous patterns of white limbs

and backs.

This art is sexy. It's intended to promote what it portrays. But it has very little in common with modern "pornography": it would be absurd to see these pictures as objectifying anyone. Men and women alike are shown with a sensual imagination that is disarmingly loving. There's no violence or cruelty and above all, no sense of sin.

Sexual bliss ... Nishikawa Sukenobu, Sexual dalliance between man

and geisha, c. 1711-16. Photograph: Copyright of The Trustees of the

British Museum

Shunga was the underground art of samurai Japan. While official

culture praised Chinese Confucian values of strict morality, authority

and hierarchy, shunga prints laugh at all that and turn the official

worldview upside down. A travesty of an advice book for women mocks

conventional tips to obey your in-laws and advocates sex as the way to a happy marriage. But beyond jokes and titillation, there is in fact an ideal that blazes through these images: peace and concord are born out of sexual bliss.

Sexual bliss ... Nishikawa Sukenobu, Sexual dalliance between man

and geisha, c. 1711-16. Photograph: Copyright of The Trustees of the

British Museum

Shunga was the underground art of samurai Japan. While official

culture praised Chinese Confucian values of strict morality, authority

and hierarchy, shunga prints laugh at all that and turn the official

worldview upside down. A travesty of an advice book for women mocks

conventional tips to obey your in-laws and advocates sex as the way to a happy marriage. But beyond jokes and titillation, there is in fact an ideal that blazes through these images: peace and concord are born out of sexual bliss.

No wonder this art appealed to westerners like Toulouse-Lautrec and Aubrey Beardsley, one or two of whose shunga-influenced images are here. Its lush lines and fiery colours are truly the door to alternative wisdom.

- Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art

- British Museum,

- Great Russell St, London

- WC1

- Starts 3 October

- Until 5 January

- Details:

020-7323 8299 - Venue website

This art is sexy. It's intended to promote what it portrays. But it has very little in common with modern "pornography": it would be absurd to see these pictures as objectifying anyone. Men and women alike are shown with a sensual imagination that is disarmingly loving. There's no violence or cruelty and above all, no sense of sin.

Sexual bliss ... Nishikawa Sukenobu, Sexual dalliance between man

and geisha, c. 1711-16. Photograph: Copyright of The Trustees of the

British Museum

Shunga was the underground art of samurai Japan. While official

culture praised Chinese Confucian values of strict morality, authority

and hierarchy, shunga prints laugh at all that and turn the official

worldview upside down. A travesty of an advice book for women mocks

conventional tips to obey your in-laws and advocates sex as the way to a happy marriage. But beyond jokes and titillation, there is in fact an ideal that blazes through these images: peace and concord are born out of sexual bliss.

Sexual bliss ... Nishikawa Sukenobu, Sexual dalliance between man

and geisha, c. 1711-16. Photograph: Copyright of The Trustees of the

British Museum

Shunga was the underground art of samurai Japan. While official

culture praised Chinese Confucian values of strict morality, authority

and hierarchy, shunga prints laugh at all that and turn the official

worldview upside down. A travesty of an advice book for women mocks

conventional tips to obey your in-laws and advocates sex as the way to a happy marriage. But beyond jokes and titillation, there is in fact an ideal that blazes through these images: peace and concord are born out of sexual bliss.No wonder this art appealed to westerners like Toulouse-Lautrec and Aubrey Beardsley, one or two of whose shunga-influenced images are here. Its lush lines and fiery colours are truly the door to alternative wisdom.

No comments:

Post a Comment